History Preserved At 565 Broadway

By MARY VAUGHAN

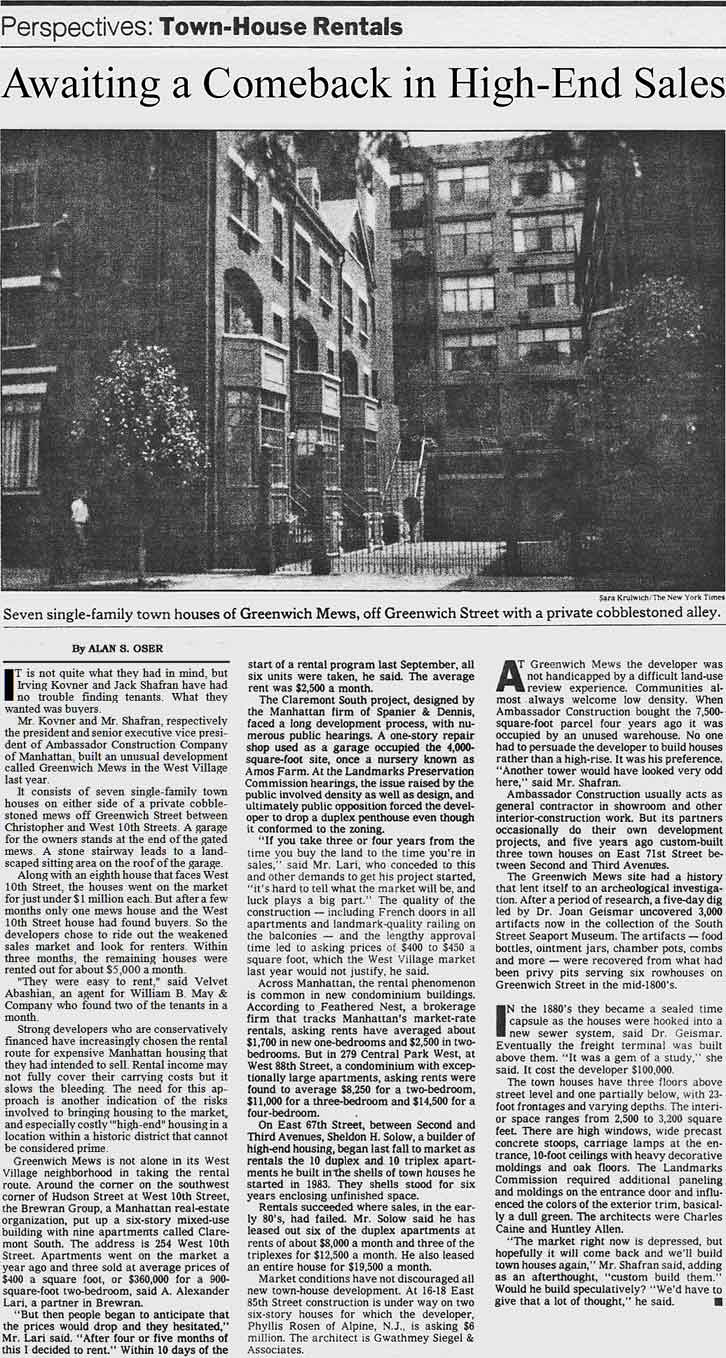

In 1860, on New York's premiere thoroughfare, a building was built on Broadway at the southeast corner of Prince Street. It was the finest business structure and most famous shop of its time, built by Ball Black & Company. A jewelry firm that began as Marquand and Co. in 1810 then became Ball Thompkins & Black in 1833 and was succeeded by a larger shop in 1860, Ball Black & Company, which built the premiere building at 565 Broadway.

A sculpted golden eagle stood on the top of the building and on top of the portico. This was the symbol of Ball Black and Company. It became the signature of the finest and oldest jewelry firm in the country, as well as the finest business structure of the time. Inside, Ball Black & Company carried on a jewelry business which catered not only to the entire United States, but extended to England as well. The firm is now known as Black Starr and Frost and has been located at Fifth Avenue and Forty-Eighth Street since 1912.

Magnificence And Prosperity

Five-sixty-five Broadway, an elegant Italianate white marble building complete with large arches flanked by Corinthian columns, charts history not only for Black Starr and Frost, but it also parallels the history of New York. The portico was described by Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper on October 6. 1860, "as a perfect temple in itself forming an appropriate entrance to the gorgeous display of jewelry and works of art within." Imagine the fashionable ladies with parasols itml gentlemen in top hats stopping in their carriages to look at the jewels through the large arched windows.

The architect who desigiwd this 1860 masterpiece was John Kellum. Kellum, a carpenter from Hempstead. Long Island, trained himself to be an architect by studying pattern books (as was common with most American architects at the time). Only Europeans or very wealthy Americans could afford the training and travel to study archilecture formally. Kellum designed Brooklyn Borough Hall and the " Boss Tweed " or New York County Court House, and planned the physical layout of Garden City, Long Island. He also designed the original New York Stock Exchange built in 1865, which has since been demolished, on the site where the current NYSE stands on Wall Street.

Kellum used a white or light pink marble for 565 Broadway. Marble was not used for many buildings in the 1800's due to expense. It is theorized that Kellum and Boss Tweed had a financial interest in a local quarry in Westchester County called Eastchester or Tuckahoe, now commonly called Westchester Marble. This quarry produced an inferior marble which was porous and had iron pigments causing a soft pinkish discoloration to the stone. Moisture seeped into the porous stone and caused the iron deposits to rust, thus expanding and cracking it. Since the same stone was used for such monumental buildings as the Ball Black and Company building at 565 Broadway, the "Boss Tweed" Court House and Brooklyn Borough Hall, it ts thought that there might have been some financial incentive behind using the inferior marble.

Not only was 565 Broadway one of the few marble buildings in New Yotk City at the time it was built, but it remains one of the few marble buildings in the Soho Cast Iron Historic District. Also the first fireproof building in New York, the sprinkler system is still intact and working. In the Ball Black and Company vaults, the modern safe deposit system was originated. It was specially inspected by the Prince of Wales on his visit to the United States and is the scene of Thomas Nasts' famous painting of the Seventh Regiment's departure for the Civil War. Black Starr and Frost has recorded all these special characteristics in a short history of the oldest jewelry house entitled At the Sign of the Golden Eagle 1810-1912.

Changing Cityscape

In 565 Broadway, there are reflected many phases of the growth and development of the social and industrial life of New York City. At its beginning it was the finest building of its time and it housed the oldest jewelry firm In the country. Upon the retirement of the elder members of Ball Black & Company, Robert C. Black, son of William Black, took in as partners Cortlandt Starr and Aaron V. Frost, each of whom had been through a long period of training with the firm. Renamed Black Starr and Frost, in 1876 they participated in the uptown movement and erected a new building on Fifth Avenue and Twenty-Eighth Street, which at that time was the social center of New York City.

The social trend moving uptown led Soho to become a wholesale district. The area became less exclusive and rents dropped, thus manufacturing and textile sweatshops moved into the area. 565 Broadway housed a clockmaker and a furrier among other tenants. Later, the building became a distribution center used for storage and warehousing, but as businesses realized that cheaper anf more convenient space could be fountd outside Manhattan they began moving to the outer boroughs and New Jersey.

The once famous building began to lose its tenants. In live sixties and seventies New York artists became aware of the large warehouse spaces left vacant by manufacturing tenants. Although the area was zoned for manufacturing/commercial use, artists began to move into the old Ball Black and Company building. Since each floor hits 5,100 square feet, artists created a combined use of working and living quarters.

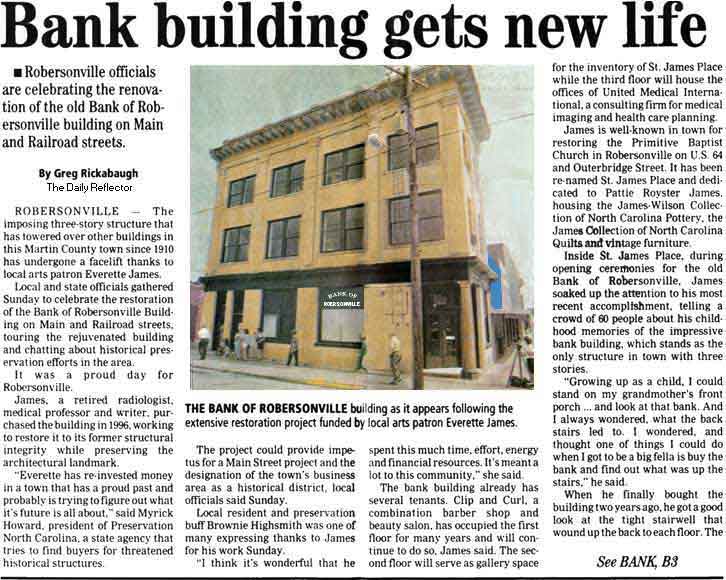

Old Bullding, New Life

By the early 1980's, 565 Broadway was fully occupied by artists. The building was required to legalize its dwelling status, which means providing proper plumbing and kitchen facilities, mailboxes, etcetera, to upgrade the raw factory space into a multiple dwelling. "This process can take several years to complete in order to receive all the approvals from the Landmarks Preservation Commission, City Planning, the Loft Board and the Department of Buildings," states Huntley Allen. Mr. Allen is the principal of Huntley Allen Architectural Services, which was hired by the tenant/owners to manage the building's conversion process and architectural restoration.

The City, aware of the changes taking place in warehouse buildings, created a zoning status called "JLWQ"—Joint Living-Work Quarters for artists. This status left the building in a quasi-manufacturing status because many artists do metal work, create stage sets and other artwork requiring large space, while enabling them to live where they work. The City wanted to make sure that only artists benefitted from the status "JLWQ" and enforced a law whereby the artist's work is reviewed and then certified by the New York City Department …