THE new cornice at the nine-story 565 Broadway is a relief from the bare cement that it replaces, but the story behind it has a lot to do with cash and little to do with good intentions.

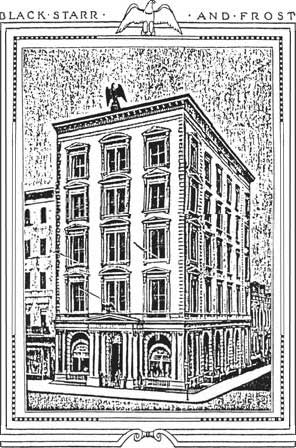

View of 565 Broadway, at Prince Street, in 1895.

View of 565 Broadway, at Prince Street, in 1895.The building's cornice is now under restoration.

(Office for Metropolitan History)

A five-story marble palazzo at the southwest corner of Prince and Broadway, designed by John Kellum, was put up in 1860 by John A. May.

For May, an umbrella manufacturer, this was a real estate operation and the building was net leased to Ball, Black & Company, a jewelry firm and silversmith, until 1874.

In 1893 Charles and Moritz Freedman bought the building for their ladies' wear business. They at first proposed adding one story but revised that to four at a cost of $50,000. Their architects, Little & O'Connor, added those four stories and faced them in cream-colored brick, gave the windows trim in imitation of that on the original building and added a projecting metal cornice. Their addition is unusual—a typical alteration in this period remade the entire façade—and it is an agreeable curiosity.

The Freedman brothers went bankrupt in 1900 and were followed at 565 by other businesses. Between 1911 and 1957 the cornice on the Broadway side was removed. Address telephone directories of the 1970's show the building fairly full of manufacturers.

In 1979, 565 Broadway was converted to a residential co-op by Martin R. Fine, who was later accused by the State Attorney General of forcing it and another loft co-op into foreclosure for his own gain, a matter that is pending in State Supreme Court.

In this section of Broadway the zoning forbids straightforward residential conversions; a building like 565 is supposedly reserved for manufacturers or working artists, who are often priced out of the market by residential tenants.

At the time of the conversion, Mr. Fine donated a façade easement on the building to the New York Landmarks Conservancy, a private nonprofit preservation group. It gives the Conservancy control over the façade; in return, Mr. Fine was able to declare a tax deduction for the reduced value of the building. The easement essentially duplicated the existing protection of the Landmarks Preservation Commission's SoHo historic district, designated in 1973, with one exception: Mr. Fine promised to restore the missing Broadway cornice within 18 months.

He never did, even after years of litigation by the Conservancy, which has accepted about 20 other façade easements without incident. Susan Henshaw Jones, executive director of the group says: "We found out that these affirmative covenants are very hard to enforce in court; they're only as good as the guy on the other side of the table."

565 Broadway as it appears today (2009) after restoration.

565 Broadway as it appears today (2009) after restoration.Apartments sell for over four million dollars apiece.

[This photo was not in the article as written in 1992]

The co-op corporation also was reluctant to restore the cornice; as recently as last year it proposed to simply remove and store the remaining, deteriorated Prince Street cornice, without any firm date for restoration.

BUT now the entire cornice is going back, at a cost of $120,000, according to Owain Hughes, the building's managing agent. To satisfy the easement? For esthetic reasons? No—to increase the sale value of apartments.

New York City zoning has an unusual provision that lets the Landmarks Preservation Commission ask the City Planning Commission for a zoning exemption for a landmark if it serves a specific preservation purpose. This is usually interpreted as a major façade restoration, but 565's deteriorating façade is going to remain as is; the commission agreed to make the application for it if the co-op restored the cornice.

The projected exemption will legalize the status of the apartments, which, because their conversion contravened zoning rules, are more difficult to sell and almost impossible to finance. Myrna Seva, an associate broker with Sinvin Realty, says that a top‑floor apartment at 565 sold recently for $995,000 and that legalization will increase values 10 to 20 percent.

In a recent interview, Mr. Fine said he didn't actually take any tax deduction for his façade easement. Ms. Jones says the Conservancy no longer accepts façade easements without a substantial cash contribution to cover the cost of administration. Mr. Hughes in turn complains that the Landmarks Commission's insistence on custom-made decoration for the cornice greatly increased the expense of the project but, he allows, "it does vastly increase the value of the building."